Bring the Pain

Our modern predicament is defined by our aversion to pain

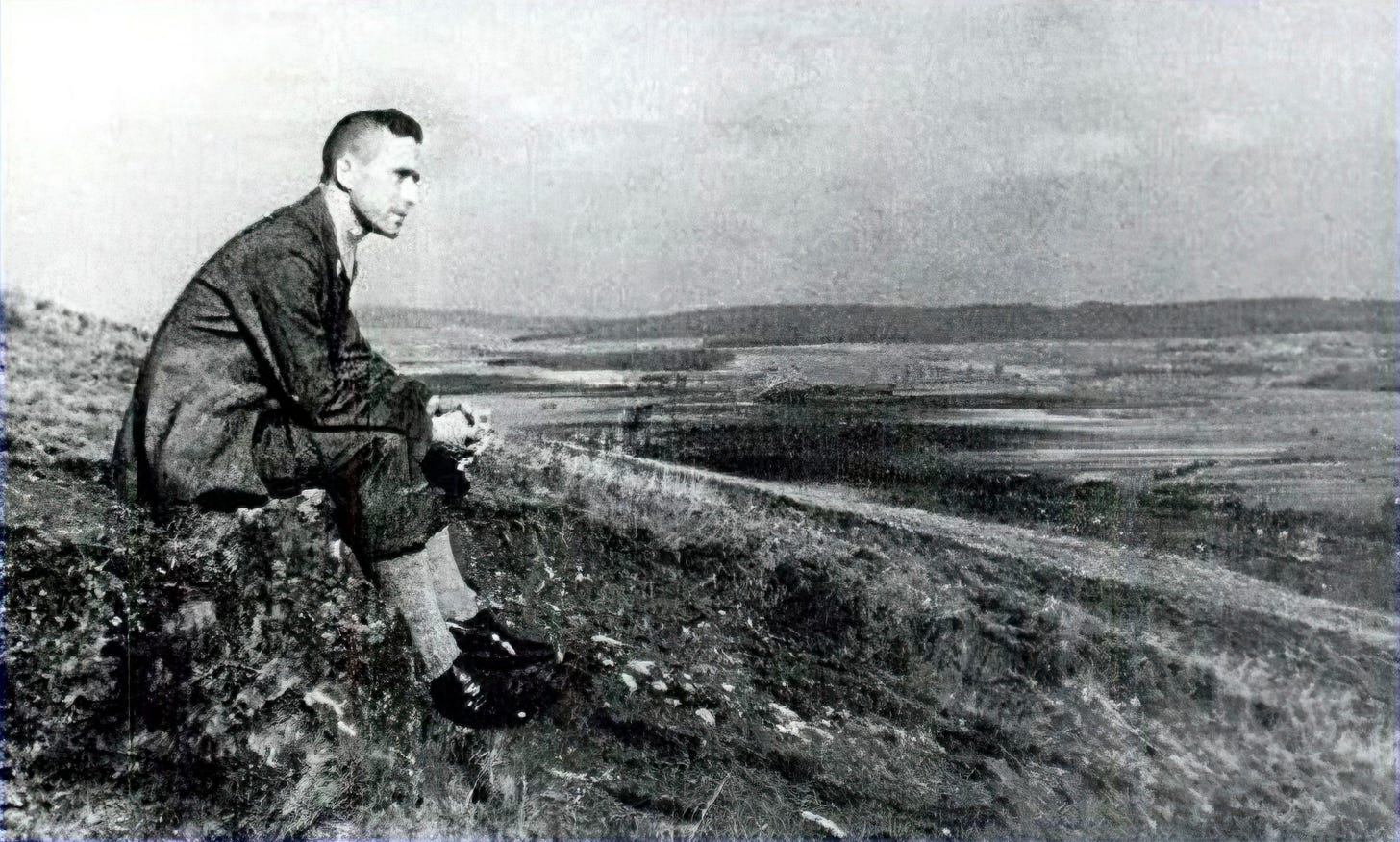

This is a new essay I’ve been thinking about for some time. I’d like to write an entire book on the subject of pain—on its history and our changing attitudes towards it—because, like Ernst Jünger and Ivan Illich, I think our aversion to pain is maybe the most crucial issue of our time. It explains the growth of medicalisation, dubbed “iatrogenesis” by Illich, which now represents the greatest threat to our freedom and way of life.

“Tell me your relation to pain and I will tell you who you are!”

For Ernst Jünger, this was true not only of individuals—we each have our own thresholds—but of entire cultures and civilisations too. Pain is a key to understanding a culture or civilisation’s power; to understanding what it truly believes and values, or doesn’t, and what it is capable of.

If this is so, what does our present relation to pain, as a civilisation, tell us about who we are? What are we capable of—or not?

*

Pain itself, according to Jünger, is “ineluctable.” It simply is. Man cannot do away with pain.

What can change, however, is man’s relationship to pain: how he rationalises it, what purposes and goals he makes it serve.

Does man elevate himself through pain or debase himself in fear of it? Does he twist himself in knots to avoid it, and in the process create new forms of pain he scarcely could have conceived before?

Pain tells us who we are.

But even so, there is something about pain—its “ineluctability”—that means it will forever retain the capacity to surprise and punish us, however we choose to position ourselves in relation to it and whatever we choose to make our pain say about ourselves. “Pain repudiates our values,” Jünger says. Pain will always escape our grasp and, if it “wants” to, embarrass us and hurt us in our fleshy, finite being.

The Enlightenment produced the belief—the mistaken belief—through faith in reason that pain could one day be eliminated for good. This attitude is, of course, a novelty in history. The “estimation of pain” has varied widely across time and place, but no civilisation apart from our own has waged war on pain as we do.

Jünger talks about the “heroic” and “cultic” worldviews, which see pain as either something to be mastered and overcome—the warrior’s “discipline”—or simply embraced and endured, as in the early Christian’s self-mortification or even martyrdom. There, in the hands of the warrior and the religious, we see the integration rather than the avoidance of pain.

“The heroic and the cultic world presents an entirely different relation to pain than does the world of sensitivity [i.e. our world]. While in the latter, as we saw, it is a matter of marginalizing pain and sheltering life from it, in the former the point is to integrate pain and organize life in such a way that one is always armed against it. Here, too, pain plays a significant, but no doubt opposite, role. This is because life strives incessantly to stay in contact with pain. Indeed, discipline means nothing other than this, whether it is of the priestly-ascetic kind directed towards abnegation or of the warlike-heroic kind directed toward hardening oneself like steel. In both cases, it is a matter of maintaining complete control over life, so that at any hour of the day it can serve a higher calling.”

For the most part, Jünger, in his gnomic way, is concerned in his essay “On Pain” with revealing the paradoxes of modern man’s relationship to pain, how with the attempt to marginalise pain it returns instead “with compound interest.” He traces the emergence of a new type of person, “the worker,” a product of modern mass democracy and industrial capitalism, with his own peculiar bodily stance towards pain, as revealed in the activities of factory work and war.

For modern man, one form of “compound interest” on pain is boredom, Jünger says. It is a product of sealing life off from the “elementary forces” including pain, and is its own form of pain—a sort of slow bleeding of life devoid of meaning. Another form comes courtesy of modern technology—from the automobile and the aeroplane to activities like mining—as it creates new and horrifying possibilities for pain and death, which we have quickly come to consider “acceptable” and just part and parcel of modern life.

*

Jünger, writing in the aftermath of the First World War, believed “the biased belief that reason can conquer pain” had now lost its “allure.” He believed new attitudes to pain were stirring, with new possibilities for man. Heroic possibilities, perhaps.

In truth, however, a century later it looks like nothing of the sort has happened, and instead we have become more deeply in thrall to the Enlightenment’s belief in the superfluousness of pain, and therefore the need to banish it, than ever before.

Our aversion to pain is now our defining predicament—the case for this was made, quite convincingly, by the philosopher Ivan Illich, in his famous book Medical Nemesis, first published in 1975. Illich argues that the modern condition is defined by the Enlightenment’s dream of eliminating pain, which traps man ever more firmly within the grasp of the medical industry. He calls this “medical nemesis” or “iatrogenesis.” It’s worth noting that Jünger only very briefly mentions the medical profession in his essay “On Pain,” with passing references to anaesthesia and vaccines, but nothing more.

Illich has been spectacularly vindicated on the subject of medical nemesis by the events of the last four years. Medicalisation and the expansion of medical control over our lives indeed represent the greatest threat to freedom we face today. For three years, medical professionals and pharmaceutical companies were given unheralded powers to define the scope of our lives, to set the boundaries of our action—to tell us who we could associate with, when, where and how, to tell us whether we could even leave our own homes and under what conditions—and to punish us for infringements against the new rules they had created. Those powers have not been relinquished, not in any real sense, and the next pandemic—which we are promised, under the sinister rubric of “Disease X,” is already on its way—will follow exactly the same pattern as the last: this is all but certain. The models of social and informational control pioneered during the pandemic are already being deployed in a wide range of new settings to police and direct our behaviour in ways the majority of the public aren’t even aware of.

If Illich were alive today, there can be no doubt he would see the COVID-19 pandemic as a turning-point in the history of our relation to pain and its shaping influence on our culture and civilisation.

In Medical Nemesis, Illich starts his analysis with more commonplace, common-sense forms of medical harm, but after making the case that public-health campaigns like mass vaccination have not been the roaring successes we’re led to believe, he begins to describe something far worse than side effects from medication or needless surgery.

There is a much more insidious, much more harmful form of iatrogenesis Illich calls “cultural iatrogenesis.” This is something broader, systemic. It’s about the power of medicine to strip us of our agency and limit our freedom to act, and in doing so to make our lives empty and meaningless. Cultural iatrogenesis “sets in when the medical enterprise saps the will of people to suffer reality.”

Culture, Illich says, “makes pain tolerable by giving it meaning.” But this is precisely what modern medicine denies: that pain has meaning. “Medicalization represents a prolific bureaucratic program based on the denial of each man’s need to deal with pain, sickness and death.”

Illich invokes what Jünger called the “cultic worldview” to explain the difference between then—the pre-modern age—and now. In the Christian Middle Ages, it was simply unthinkable to believe pain was something that could be “destroyed.” Pain was to be “suffered, alleviated, interpreted”—but never, ultimately, to be destroyed by any means let alone technical intervention. There would be an end to pain, but only for the faithful who made it to heaven. For the medieval Christian, pain on earth was a “sanctifying backlash against sin,” a test for the sufferer, exactly as it was for Job. The religious “duty to suffer… challenges the sufferer to bear torture with dignity” and to maintain their faith in God.

The great change came with the Reformation and Enlightenment. Over time, with the fragmentation of Christendom and the retreat of religion from public life, pain was stripped of its religious meaning. It became secularised. It was no longer “mystical.”

By becoming secularised, pain was made irrational, and the great aim of Progress, the new secular religion, is to eliminate the irrational wherever it is found. Pain became something that could be “verified, measured and regulated,” but only in the interest of removing it. This is where our modern crusade against pain began.

There is a direct line, in this account, from those changes that took place in our attitude towards pain to the medical tyranny established during the pandemic, the threat of whose restoration now hangs over us, like the proverbial sword, at all times. Medicine could not have become a massive apparatus for social control if we had not first surrendered the notion that pain can have meaning and a purpose.

So what can we do?

Can we reconsecrate pain, as it were, and give it new meaning—and by doing so remove it from the domain of the irrational, so that it ceases to be just an object for technical intervention? This is the question.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In the Raw to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.