ANCESTRAL EATING: The Case for Raw Milk

Let's look at a very well-argued case for raw milk from the 1940s

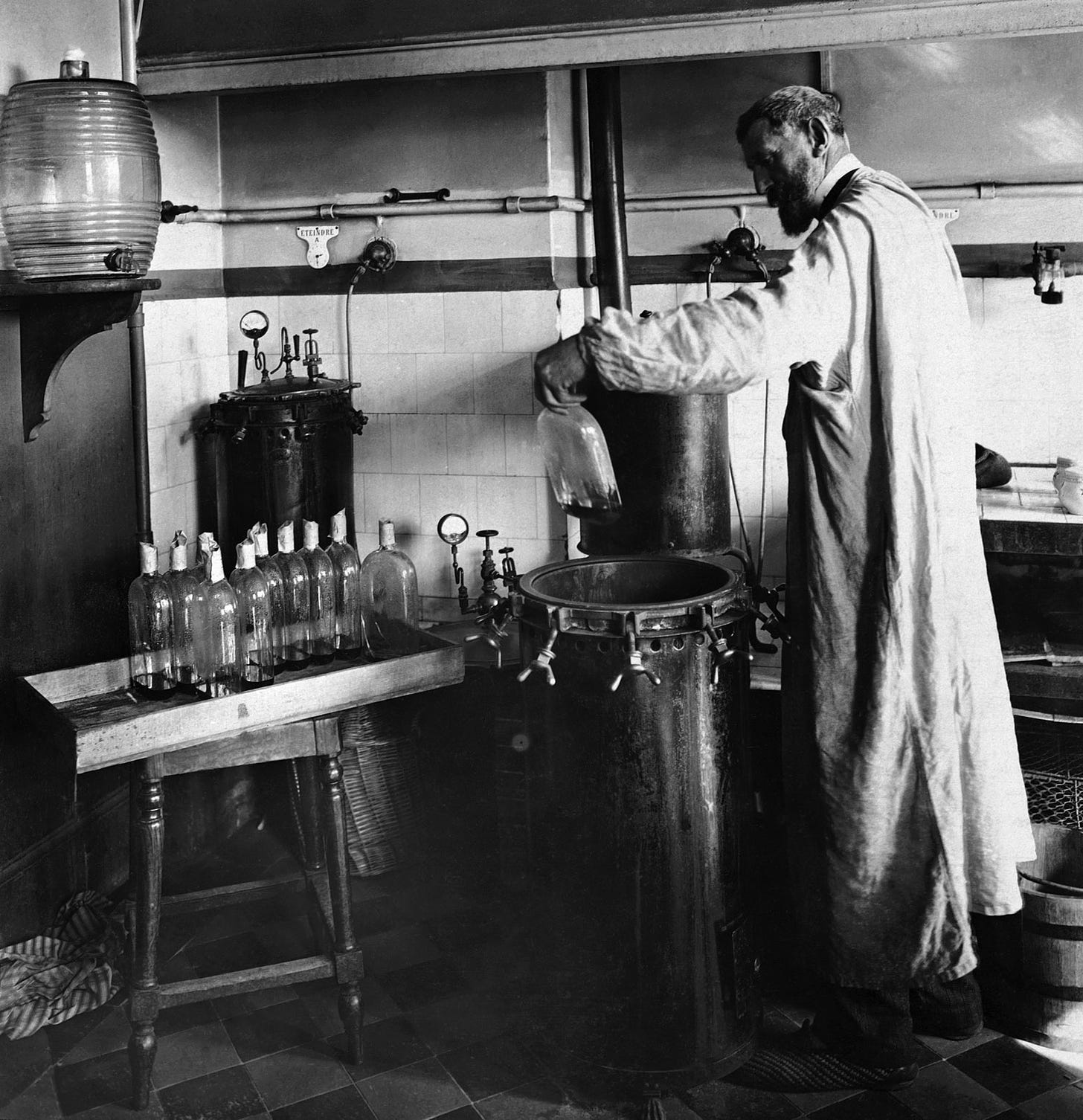

What follows is an important primary source for understanding the historical context of pasteurisation. It’s an article written by a South African doctor called L. Erasmus Ellis in the late 1940s, in which the author argues against the pasteurisation of milk.

The article illustrates a number of points that I made in an earlier post about the history of pasteurisation, not least of all the fact that its introduction had as much, if not more, to do with satisfying the needs of corporate milk producers as it did health concerns about e.g. tuberculosis. Put simply, corporate milk producers and distributors wanted a product that they could store and ship long distances easily, and raw milk was not that product. It wasn’t that product then, and it isn’t now.

Ellis not only advances a powerful, cogent argument against pasteurisation on health grounds, both for humans and the cows producing the milk, but he also makes a strong case that a nationwide system of raw milk production and distribution, which would also cater to the needs of large towns and cities, would be perfectly feasible.

Once again, as in the case of Francis Pottenger, it’s worth reminding the world that it wasn’t cranks and weirdos and “right-wing conspiracy theorists” (thanks, Politico!) who were arguing against pasteurisation in the early decades of the 20th century, but highly qualified, well-respected medical professionals who simply did not believe, on the basis of a variety of evidence, that widespread pasteurisation was a good idea. Ellis believed that in some situations it could be warranted, but that blanket pasteurisation would be detrimental to health.

Next week I’ll be wrapping up this mini-series on dairy and raw foods with a piece about why milk and milk products make you feel so good when you consume them (hint: it’s got something to do with opioids).

A controversy has arisen in Britain and also in South Africa upon the important problem of a clean, fresh milk-supply versus the pasteurizing of all milk.

Speaking generally, a fresh milk-supply is advocated by the producer-distributor, while pasteurization is advocated by the large combines and milk-distributing companies, in many of which the Prudential Insurance Company holds large interests. The material for conflicting interests is obvious as between these contending organizations.

The following data bearing upon this subject are taken from “Control of Life” (1944), by Halliday Sutherland, M.D ., who is a world-wide-known authority upon matters of hygiene and medical social economy generally. (Cf. “Control of Life”. Chapter S, pp. 71 to 85).

Doctor Sutherland points out that milk is a staple and almost ideal food, containing at least six vitamin in addition to proteins, fat, carbohydrates, calcium and phosphorus.

In Britain the milk combines, in 1938, by their pasteurized milk propaganda, provoked a controversy which has become a fight to the finish between a clean, fresh milk-supply and compulsory pasteurization. Doctor Chalmers Watson, the famous dietitian, wrote to the B.M.J. in 1938, warning medical men who advocate pasteurization of milk that they are not politicians, and that they should be cautious and not unwittingly support legislative measures which may be more useful to political parties than to the general public. This appears to be a very subtle point.

Pasteurization of milk as carried out in a scientific laboratory may be quite sound and efficient. but when conducted commercially, and in South Africa, largely by Natives, there may be serious pitfalls. Such pasteurized milk, before it reaches the consumer, on occasions shows more contamination than clean fresh milk. When it goes bad it stinks, and cannot be used for “Maas”, as clean sour milk can be used.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In the Raw to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.