ANCESTRAL EATING: Dairying and the Indo-Europeans

Dairy consumption is, quite literally, one of the great engines of history. Just ask the Yamnaya...

Welcome back to ANCESTRAL EATING, my friends. We’re talking about dairy today and the amazing and under-appreciated role it plays in world history. Cutting-edge genomic studies are showing that the emergence of dairying on the Eurasian steppe was the catalyst for one of the most important migrations of all time.

Before I tell you about it, though, let me just remind you that you can get 15% off a full year’s subscription to my Substack if you click the following button before the end of the month (March 2024):

I

Hard is the life when naked and unhouzed

And wasted by the long day's fruitless pains,

The hungry savage, 'mid deep forests, rouzed

By storms, lies down at night on unknown plains

And lifts his head in fear, while famished trains

Of boars along the crashing forests prowl,

And heard in darkness, as the rushing rains

Put out his watch-fire, bears contending growl

And round his fenceless bed gaunt wolves in armies howl.II

Yet is he strong to suffer, and his mind

Encounters all his evils unsubdued;

For happier days since at the breast he pined

He never knew, and when by foes pursued

With life he scarce has reached the fortress rude,

While with the war-song's peal the valleys shake,

What in those wild assemblies has he viewed

But men who all of his hard lot partake,

Repose in the same fear, to the same toil awake?William Wordsworth, Salisbury Plain

In my most recent book, The Eggs Benedict Option, I consider the Agricultural Revolution—also called the “Neolithic Revolution,” the emergence of fixed-field farming and animal domestication in the Near East, c.10,000 years ago—as one of the pivotal events in human history.

Of course, I’m hardly the first person to think of the Agricultural Revolution in these terms. It’s quite obvious that, without farming as a distinct mode of subsistence, our world simply wouldn’t be the same. Our world wouldn’t even exist. We’d probably still be living in small, mobile bands of hunter-gatherers, as humans had for the vast majority of our history (c.200,000 years).

With the discovery of agriculture, history accelerated at a speed that’s pretty hard to fathom. From stone-tipped spears to nuclear weapons and space travel, in less than 1/20th of the time modern humans have existed.

Here’s how I put it in the book, in the first chapter, “Welcome to 2030BC: the Original Great Reset”:

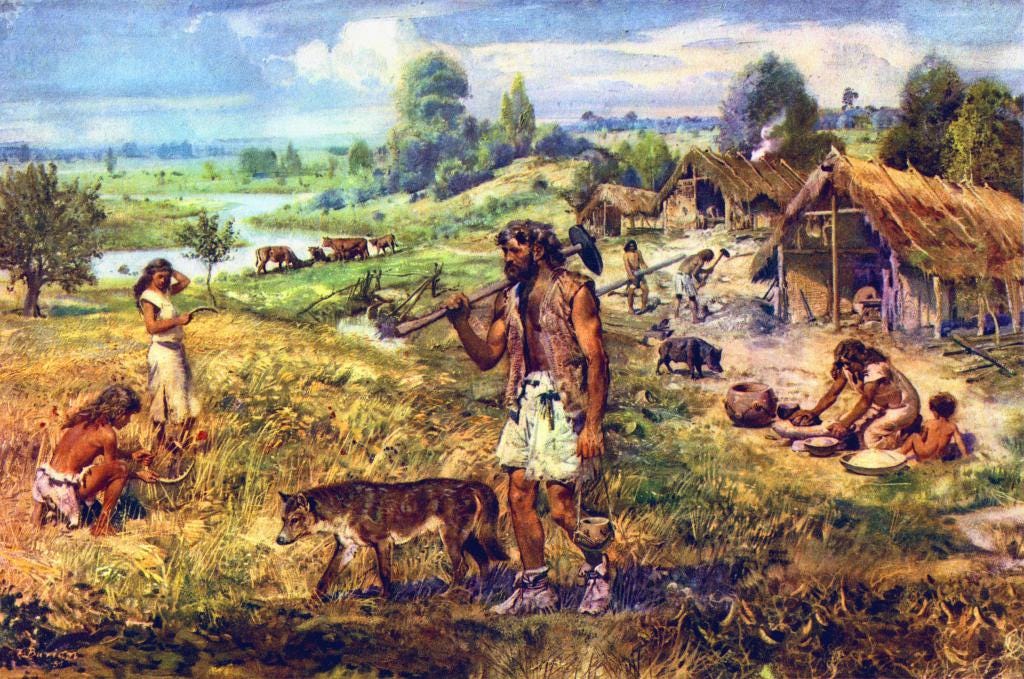

There’s a story about the birth of agriculture and it goes something like this. Before there was proper agriculture—the regular sowing of annual grain harvests—life was hard for man. Of course, life would go on being hard for man after the establishment of proper agriculture, but before that Archimedean moment, before man started cultivating grains, life was really hard. Without agriculture, primitive man was totally dependent on his ability to hunt and kill game, fish, and fowl, and to gather berries, nuts, wild honey, and tubers. All of this involved not only a high degree of fitness and skill, but a significant measure of danger too, and the best foods, meaning the most calorie- and nutrition-dense foods, came at the highest potential cost. So while a Plains Indian (a latter-day Stone Age man) might have subsisted on insects and moss if driven to it by circumstance, he would much rather have eaten fresh liver and still-beating heart and drunk warm blood—and that meant hunting buffalo on the plains or game in the forest, activities that could just as easily be fatal as unsuccessful. Thomas Hobbes said that in the state of nature—before man was subject to sovereign power (i.e. states)—man’s life was “nasty, brutish and short,” and the poet of Salisbury Plain, nor untold other poets, artists, philosophers, and thinkers, didn’t disagree either.

By contrast, grain agriculture brought abundance and regularity, and with abundance and regularity, safety. Man could predict and master nature, and therefore his own destiny, in a way that simply had never been possible before that moment. With enough seeds and a proper understanding of the seasons, man could produce a regular harvest of nutritious food that didn’t require great physical prowess or bravery—just a certain amount of drudgery—to produce and gather. And who wouldn’t prefer a little drudgery over a hunting wound that, if not immediately fatal, would likely fester and still prove a death sentence all the same? A predictable food supply, barring the occasional crop failure, meant larger populations could be sustained. It meant other things too. It meant that man could get to thinking about and doing the things that really matter: like building towns and cities, for instance; like developing new technology and engaging in commerce, scholarly pursuits, and education; civilization; progress; man’s inexorable destiny. In short, man was—and is—much better off as a cereal-cultivating, sedentary creature than he had been as a fully or semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer.

Societies tell themselves stories that justify their institutions and history, whatever they may be, and we are products of the great agricultural revolution as much as Thomas Hobbes, William Wordsworth, or the first farmers of the Near East. No healthy society willingly portrays itself as being on the wrong side of history (which is why the new origin stories Americans tell themselves, like the 1619 Project, are so revealing). And, to some extent, such stories must be true. Ideologies have to be, for people to believe them, at least in the long run. Dispute its benefits all you will, but there’s no disputing that grain agriculture radically changed the world. How different the world would be without it, we can scarcely imagine. If you want to try, though, imagine sustaining large urban centers or cities in any other manner. How would it be done? A history of civilization without cities is, for many, an oxymoron.

Farming allowed the emergence of the first urban centres and the first cities, like Ur and Uruk, which had unheralded concentrations of people. Before the Agricultural Revolution, hunter-gatherer groups probably moved around in groups in the low hundreds, but the first cities contained as many as 50,000 people within their walls.

My interest in the Agricultural Revolution, at least in The Eggs Benedict Option, is as part of a deep history of the relationship between control of the food supply and control of society. This relationship was first explicitly theorised, as far as I can see, by Plato in the Republic (c.330BC), through his thought experiment about the “Republic of Pigs,” a harmonious society that was kept in check solely through a strict vegetarian diet. But food was being used as a method of control thousands of years before that, from the very moment fixed-field farming started to be used to produce reliable surpluses that could be stored, managed and distributed by new elite groups within society.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In the Raw to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.